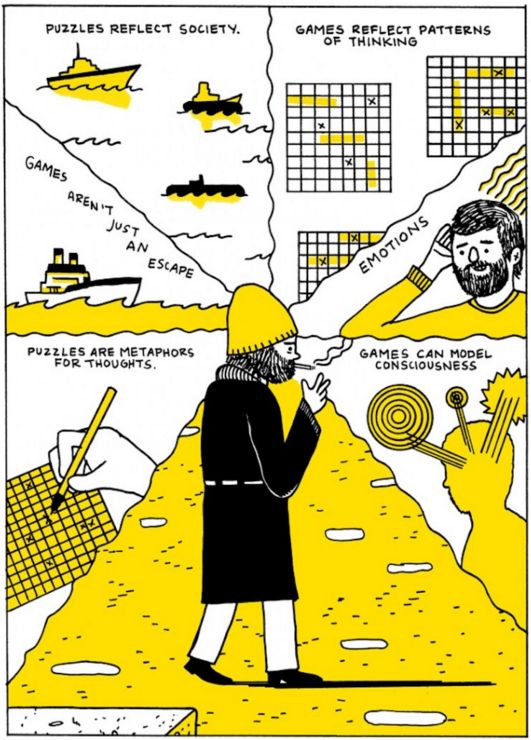

I just finished an amazing graphic novel called Tetris: the Games People Play, by Box Brown.

At first blush, I thought reading a graphic novel about a video game would be like watching a dance about architecture, but the awesomeness of Tetris is conveyed rather well in this entirely two-toned, historically accurate account of the international drama that surrounded the game Tetris in the late eighties and early nineties.

The story details how ELORG, a repressive Soviet government entity, handled the rights for Tetris, and how unscrupulous businessmen in the west exploited contracts to sell the rights for Tetris to other companies who then went on to unknowingly publish Tetris illegally. It’s a delicious setup with plenty of colorful characters, greed, intrigue, and friendship. It’s also a fascinating primer on the history of Nintendo and their rivalry with Atari and other nascent video game makers in the late eighties.

But before there was Tetris fever, Alexey Pajitnov, a computer scientist at the Moscow Academy of Science, was an ordinary comrade who thought deeply about games.

Alexey believed that puzzles were crucial to an individual’s mental well-being. Like tiger cubs play-fight in preparation for hunting in adulthood, games and puzzles model consciousness, preparing our minds for real-world problem-solving, giving us the tools and mental muscle to handle the greatest puzzle: life.

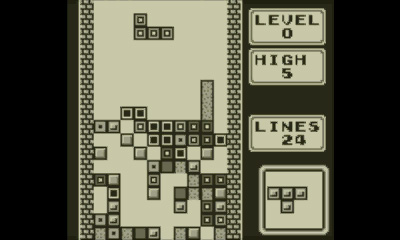

I loved Tetris as a kid. I still have my Game Boy. And though the pins of the Tetris cartridge are permanently fused to the game unit, everything still works!

As I’ve been playing the game recently, I discovered that in any given Tetris game, I cycle through a handful of mental states. Always in the same order, kind of like the stages of grief. Except they’re the stages of Tetris.

It further occurred to me that these stages, the feelings I get from playing Tetris, mirror different phases of my day. For example:

Phase 1: The Game Begins. From 6am-9am, this is pretty much my state of mind. This isn’t me every morning, but it is me on a good morning (when I’ve prepared coffee the night before and have gotten sufficient sleep). Just look at all that white space. So clean and orderly. So much potential! I’m ready for whatever tetromino the world has to throw at me!

Phase 2: 9am-12pm. Everyone flubs a few Tetris blocks every now and then, right? This is the part of the game where you say to yourself, “Okay, enough waiting around for long piece, time to get down to business and focus on fundamentals by eliminating one line at a time.” The real-life correspondence here is that a few early-morning tasks didn’t get done, others took longer than expected, the kids are playing in mud again, but I can still get back to my original, pristine, meticulously-time-blocked schedule if I dig deep and try really hard. Right?

Phase 3: 12pm-3pm. Oh, dear. This is the part of the game where things go off the rails. Many things have not gone the way you planned, so you shift from strategy to triage. No more lofty notions of getting ahead on that work project, or even actually finishing everything on your to-do list for today. This is the time when every move is a gambit for your own survival. You can still make it. Maybe. Hopefully. If not, there’s always tomorrow.

Phase 4: 3pm-6pm. Aaaaahhhhhh! We’re beyond triage. We’re in pure survival mode, and we’re failing. Every game must come to an end. And every game of Tetris ends in tragedy. This is usually the “I’ll do better tomorrow” part of my day where I call it a day, assess my wins, and realize that even though I didn’t feel a sense of progress in the moment, I didn’t do half-bad today.

But sometimes, at the out of the blue, you get a late-in-the-day win:

Bam! Long tetromino for the win. This is usually a result of ignoring all the other things I have to do and doubling down on completing one more thing. If I can do that, I usually call it a win.

No analogy is perfect, and the Tetris analogy for daily stress doesn’t cover all the bases, but it’s a fair approximation of my mental state.

When Alexey Pajitnov says (in the book) that games model both individual thought and society, and can model human patterns of thinking, he’s not just talking about games. He’s also talking about art. Games are art. This is a big theme of the Tetris book.

Fiction is one of my preferred mediums for engaging in art. Storytelling, like Tetris, mirrors the human experience for the listener or reader. But what about the author? Does the process of writing model human consciousness the same way experiencing stories does?

For me, yes it does. With any story (or game of Tetris, for that matter) that I endeavor to set down in words, I find there are some common components:

1: Joy in the process of discovery, the delicious promise of potential. For me this is the beginning phase of “discovery writing.”

2: Conflict or tension builds due to progressive complications. i.e. things not going according to plan. For example, I’ll get a third of the way into writing a draft of a book and will lose steam.

3: Decisions must be made that could change my approach dramatically. In revising, I might realize I have to cut a whole character or subplot arc.

4: Despair. That sinking feeling that nothing is going right, my ambition is three times the size of my skill level, and I’m in way over my head. For me, this is the editing phase and it feels soooooooooooo slow going and overwhelming.

5: Epiphany when I finally find a way to make a plot arc or character come to life. This is often the result of many hours of banging my head against a wall (see #4). The feeling of finding my way out of the slum is pretty much exactly like getting a long tetromino and digging myself out of a Tetris mountain.

So, what is the point of linking the process of writing and Tetris? Games, stories, and art are ways that we can simultaneously take a break from the human experience while, paradoxically, engaging it on a deep level through another medium. Perhaps we don’t ever really need a break from reality, we just need a shifting of our perspective to get our heads right every so often. Tools like books, theater, music, graffiti, video games, paintings, sculpture, movies, and binge-worthy TV all offer perspectives on consciousness that break us free of our own ways of thinking about the world.

Since most people are forced to remain indoors these days, I’d think a lot of folks are growing introspective about their lives and their choices. But I think it’s valuable to consider what we’re reaching out for. I have friends who have said that they are reading and watching a lot more fantasy lately because, well, realism is just too much right not. I find myself thinking about games and puzzles.

If you take a moment to think about what kind of art you are consuming, what do you find yourself drawn to? How is that art helping you find a new perspective in this new normal?